In early July 2021, former Paramount Pictures boss Barry Diller claimed, “The movie business is over. The movie business as before is finished and will never come back,” in an exclusive interview with NPR.

He goes on to say:

“These streaming services have been making something that they call ‘movies.’ They ain’t movies. They are some weird algorithmic process that has created things that last 100 minutes or so…. I used to be in the movie business where you made something really because you cared about it.”

Scarlett Johansson probably agrees. She’s suing Disney over her contract for Black Widow.

Disney released the much delayed Black Widow at the same time in cinemas and on its Disney+ streaming service for an extra $29.99, a.k.a a Day-and-Date release “potentially depriving her of a huge box-office-infused paycheck” according to The Verge.

She says her 2017 contract guaranteed an implied exclusive theatrical release although Disney decided due to the pandemic stunting box office revenue they would release the blockbuster on their streaming platform on the same day. Ironically, Disney+ only came in existence in late 2019.

This had the effect of diminishing ScarJo’s potential profit participation of perhaps $50 million, on top of her base fee of $20 million.

However, on the other hand, Wild Bunch CEO Vincent Grimond believes that if independent film companies are to survive, they need to tap into online revenues, as reported in The Hollywood Reporter.

Scott Roxborough‘s article also quotes Shudder‘s global acquisitions and co-production director Emily Gotto as saying:

“We’ve found that we can get the same awareness, the same press, and marketing attention by doing an online release, without theatrical. Especially if we are dealing with genre titles, we can put it out on our service and also go through our output partnerships to put it onto physical hard goods — DVD, Blu-Ray, in some cases even specialty VHS, while also making the film available on download to own, on Apple, on iTunes, on Amazon Prime. It’s the opportunity for the film to be seen and for the filmmaker to be seen.”

He also quotes Craig Engler, general manager of Shudder, which has over one million subscribers, as saying:

“We’re very big on doing themed programming. So we might do Werewolf Month. You might have heard of The Howling, say, so we’ll use The Howling as a way to get you to check out Ginger Snaps and other great werewolf films you might never think to search out.”

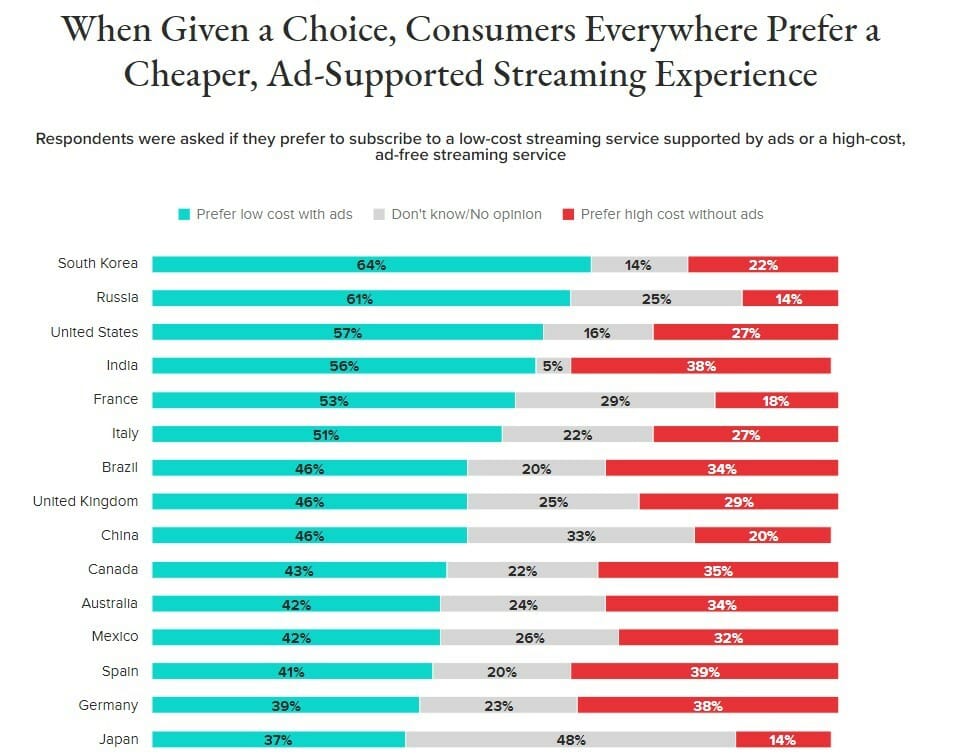

My take: The film business continues to evolve. Once upon a time it was all about bums in seats. Now it’s all about eyes on screens — and everyday it matters less and less what type of screen that is. I predict the ascent of curated streaming services because it’s easier to build niche audiences and then satisfy their specific wants than to appeal to everyone. Cinemas made sense when films were physical and had to be delivered to real buildings scattered across countries: the cost of prints and advertising could easily match production budgets necessitating popular movies that everyone would want to see. Digital delivery changes everything. Mass audiences aren’t determined by geography anymore; today it’s interests that bond folks into splintered, but sizeable, audiences.