Aleem Hossain blogs on No Film School How (and Why) I Made an Indie Sci-Fi Feature Film for $30K.

It’s a fascinating read. His belief is that:

“We should rethink why we are making independent films in the first place, especially indie sci-fi and speculative films. I don’t think we should even be trying to compete with Hollywood. We should be striving to make films that are strikingly different from big-budget films.”

Aleem faced five challenges making After We Leave and solved them creatively. Although he answers them from a sci-fi point of view, they can be extrapolated to indie filmmaking in general.

#1. The Brainstorming Phase: What Are Sci-Fi and Indie Film’s Core Strengths?

“Hollywood is very good at making its kind of movies. Why should we try to compete with them with a lot less money? In my mind, the only reason to make an independent feature film is to create a movie that only you would make. A kind of film that wouldn’t exist if you didn’t exist. I think what independent films can offer are new directions in style, tone, theme, topic, representation, and viewing experiences. They can challenge the mainstream artistically, politically, and narratively.”

#2. World building does not have to be expensive.

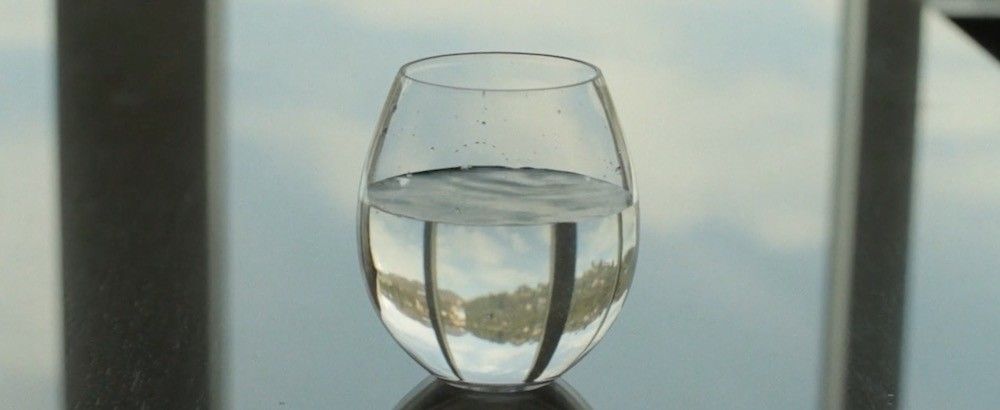

Rather than with a VFX-laden long shot, sometimes a world can be built with a carefully composed close up:

“The future version of Los Angeles that I imagine in my film is undergoing severe water shortages. This glass is the only clean water we see in the entire film. Every other time characters drink, they drink dirty water or something other than water. I don’t have a shot of a huge empty reservoir. I don’t have a shot of drones “mining” water from clouds. I have one clear glass of water, provided by the most powerful and richest character in the film… and my main character chugs it down. It cost me nothing. But it’s definitely world building.”

#3. The standard model of film production discourages artistic risk-taking.

Aleem laments, “The system is always telling us to play it safe.”

To counter the “stay on schedule” mantra, he bought their camera gear:

“We could choose to just try one crazy complicated shot, exactly at sunrise, and then we’d all go off to our day jobs. If it didn’t work we could try again the next morning. There was no downside other than our time… and because we were fitting it in around our existing work and lives. This way of working was, in fact, the thing that convinced collaborators (some long time friends, some new) to work on the film. They all had day jobs that paid way better than I could. The reason they gave up their nights and lunch hours and weekends to work on After We Leave was that I was offering them a chance to try things they normally didn’t get to try. To reach for things in a way they normally didn’t get to.”

This also freed up his actors to ask for extra takes and for his DOP to extend magic hour by shooting at the same time over a number of days.

As to locations:

“I ‘scouted’ for hours on Google Street view looking for rundown and beautifully gritty locations… and then I placed small scenes in each of them. We shot all over Los Angeles. We didn’t get a single permit. We didn’t need to because we didn’t care if we got kicked out of somewhere… it wouldn’t throw off our schedule or make us cut the scene or waste a ton of money. We’d just film it next weekend at a different location. And the truth is, most days we were a crew of three people with a DSLR, a Zoom recorder and a mic, plus one or two actors. We shot in 25 different exterior Los Angeles locations and were approached only once by the police and twice by private security. And in two of three of those times, they weren’t telling us to stop filming… they were making sure we were safe in what they perceived to be a dangerous location.”

#4. VFX don’t have to cost a lot of money, they (just) cost time.

Rotoscoping and motion tracking in Adobe After Effects have improved so much in the last ten years that green screens and locked off cameras are no longer necessary.

See their VFX reel.

#5. There is actually a huge advantage to being micro-budget when you reach the distribution phase.

Aleem realized his advantage was, “I needed to make back less money than other films.”

After being rejected by top film festivals, he found success at niche ones:

“After being rejected by 22 festivals in a row, I got an email from Sci-Fi London raving about my movie. I gave them the world premiere and After We Leave won Best Feature Film there and everything started to change. We went on to Berlin Sci-Fi, Other Worlds, Boston Sci-Fi and won a number of awards and got great reviews.”

Aleem concludes:

“The big lesson I learned is to only do what I felt we could do well and to pick a story that makes use of that. And that’s the irony… by avoiding mimicking the films that try to appeal to huge audiences, I actually created a film that resonated with audiences.”

My take: Lots to take away here. Embrace your limitations. Less money can mean more time. Raise enough to get it in the can. Then raise more to finish it. Use the right festivals to connect with your true audience. Never compromise your vision.